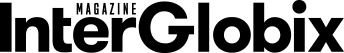

The global data center colocation and interconnection (DCI) market continues to grow amid macroeconomic headwinds and a turbulent landscape created by the after-effects of the global pandemic. As a whole, this market was estimated to be worth 64.9 billion USD in 2022, a figure that represented 13.4 percent y/y growth. Looking ahead to 2023, the market is expected to continue on its upward trajectory, growing 12 percent y/y to 72.7 billion USD. Global expansion, hyperscale consumption, uptake in interconnection, and development of Edge locations are key drivers. The five-year CAGR for the 2023–2028 period is expected to come in at 13.5 percent. In 2026, this market is on track to be worth over 100 billion USD for the first time and is projected to reach 136.8 billion USD in 2028. The numbers are all up from our previous market projections.

The data center colocation market has traditionally been separated into two distinct segments: retail and wholesale. Hyperscale colocation has emerged as a category of its own but, to this point, was grouped with wholesale colocation. In our previous report, published in early 2022, the market was split roughly 60–40 percent in favor of retail colocation. In this latest update, we have adjusted our taxonomy in order to capture the distinct differences that now exist between colocation segments.

Changing reporting categories

Our new taxonomy draws a line between enterprise colocation and hyperscale colocation. Within enterprise colocation, there are two sub-categories: enterprise retail and enterprise retail+. Enterprise retail+ captures larger colocation deployments that were typically categorized as enterprise wholesale. Enterprise retail is more or less traditional retail colocation. In terms of total market value, the split between enterprise and hyperscale is 71–29 percent in favor of enterprise. But by 2028, that split is expected to be exactly 50–50 as public cloud adoption across the board continues to drive demand for colocation.

On the hyperscale side, there are also two new sub-categories: Edge-hyperscale and core-hyperscale. The latter is clear-cut and encompasses large data center campuses and buildings housing hyperscale cloud AZs and regions. The deployments consist of tens—and soon even hundreds—of MWs. The former is a smaller increment (single-digit MWs and slightly lower than one MW) but are typically taken down by a hyperscale customer. These deployments are typically house Edge locations, network PoPs, cloud on-ramps, and proximate compute nodes that are part of a core-Edge architecture. For the 2023–2028 period, core-hyperscale is expected to grow at a five-year CAGR of 24.4 percent, while Edge-hyperscale will hit a CAGR of 31.6 percent.

Public cloud growth to continue slowing

The biggest question facing the sector moving into 2023 is around the slowing of public cloud growth, albeit off fairly high bases, given the unprecedented acceleration of cloud adoption that occurred during the pandemic. AWS, Microsoft Azure, and Google Cloud saw revenue growth slow progressively over each quarter in 2022, and that trend is expected to continue at least for the first half of 2023. The slowing in public cloud growth, needless to say, has the potential to impact multiple infrastructure segments. Data center operators are expected to see continued demand and will be engaged with hyperscale clients for long-term planning and new market entry. But the ramping pace for hyperscale deals will likely start to see extended timelines. Options to take additional capacity are starting to be pushed out, or in some cases, as with some of the Chinese cloud providers, turned down altogether.

Cloud re-balancing to pick up pace

Cloud re-balancing (or repatriation) has become an increasingly frequent topic of conservation as managed infrastructure operators see more customers moving out of public cloud. Repatriation has happened in pockets for some time, but there appears to have been a meaningful uptick over the last few quarters. Is this trend real, or is it recency bias shading perspectives and observations? It would seem to be more of the former. The intensifying focus on cost and performance optimization brought on by the current macroeconomic environment has pushed organizations to reconsider and ultimately move certain workloads off the public cloud. Some organizations are doing this as a cost-cutting measure, while others are finding that traditional infrastructure deployment models (like a private cloud) are better aligned with what they are more comfortable with. Growing numbers of organizations are finding that a predictable monthly bill, fixed infrastructure consumption, and a more interactive service provider relationship are more important than scalability and perceived pricing benefits. That is not to say there is going to be a massive wave of movement off public cloud—the re-balancing that happens will not be material to public cloud growth trajectories. But the frequency is likely to pick up pace as organizations recalibrate how they deploy infrastructure. Recalibration and workload optimization will favor hybrid deployment models, which will create opportunities for colocation providers to cater for specific high-performance computing (HPC) and enterprise workloads that may not be best suited for the public cloud.

The move away from on-premise data centers is accelerating

On-premise data centers continue to age and have not found the fountain of youth. New ones are not being built. Organizations with large investments in proprietary data centers tend to be the ones currently the most aggressive with transformation projects (and by extension, have the most upside potential for outsourcing). A tight budgetary environment is causing headwinds for new projects and expansion, but the pressure it is creating to find cost savings and operating efficiencies is persistent and intensifying. This situation has not slowed during this current period of macroeconomic uncertainty and ensures continued demand for colocation and cloud. The seemingly permanent change in how people work is another variable to consider. Commercial real estate continues to be under pressure. Running an internal data center, which is often less than efficient at the best of times, will not be viewed as a good use of real estate assets. As organizations continue to evaluate how they set up work environments, the more pressure there is to drive operating efficiency, and internal data centers are not likely to be looked on favorably. Targets around renewables, carbon footprint, and other ESG initiatives are another driver to move to newer, more efficient, and more sustainably designed third-party data centers. External forces and a fundamental change in direction are going to keep the pressure on to close and optimize on-premise data centers. The pace and intensity at which this is happening is very different from what we have seen in the past. Combining this with where IT infrastructure is going, along with how organizations are rethinking work, makes it a good bet that the move away from on-premise data centers to cloud and colocation will continue to accelerate.

Decentralization of hyperscale demand underway

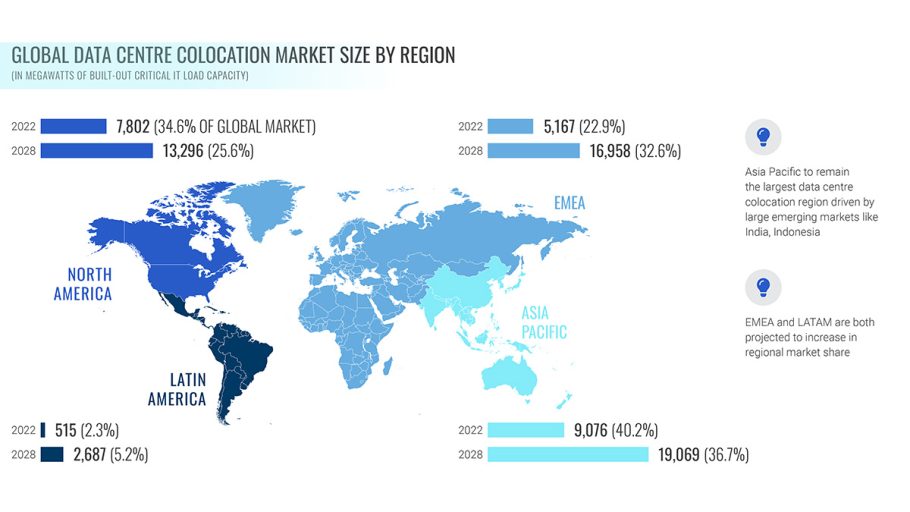

Hyperscale clouds started off centralizing their footprints and deployments in a select group of core global hubs. Asia-Pacific, Singapore, and Hong Kong are prime examples of this initial strategy, given their positions as connectivity hubs with a high concentration of international submarine cables. Internet infrastructure will continue to shift to a more distributed and decentralized model. More submarine cables are being constructed to connect emerging markets to core markets. This approach will lead eventually to a shift in data center builds and deployments to more localized and in-country architectures. Hyperscale clouds will continue to fill gaps in their infrastructure map, especially in markets with large population densities like Indonesia, India, South Korea, and Japan. Hyperscale clouds have shown the appetite and ability to build their own data centers in APAC and may continue to do so in the future. This build would cannibalize some demand from colocation data center providers if hyperscalers choose to build their own data centers.

Complexity of decentralization driving near-term boost in overflow markets

The path to decentralization for many of the hyperscalers has taken longer than initially predicted as they underestimated the complexity of deploying network architectures at scale and with the proper amount of resiliency and reliability. Instead, hyperscalers seem to prefer finding ways to extend their data center capacity across existing core hubs or regions where they have already established core network nodes or network aggregation points. This is why Johor in Malaysia has seen such an acceleration in demand and development activity, and also why markets like Melbourne (Australia) and Osaka (Japan) are experiencing notable cloud infrastructure demand.

Hyperscalers moving more convincingly to the Edge will create more opportunity for colocation providers

Hyperscale cloud infrastructure is, by nature, highly centralized to take advantage of economies of scale. A number of factors are driving a move to a more decentralized model, as public cloud adoption continues to accelerate across both mature and emerging markets and customers demand increased performance, especially in markets that don’t yet have in-country public cloud infrastructure. It is unlikely that hyperscale clouds will build in smaller increments at the Edge because that would not scale efficiently. But they are building different scenarios through the deployment of converged infrastructure appliances. AWS Local Zones are basically an Edge data center—via colocation—with Outposts appliances set up and connected back to a cloud region. Microsoft launched Azure Edge Zones, a small increment of compute located in its Edge PoPs and now moving into wireless carrier PoPs.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Jabez Tan is Head of Research at Structure Research, an independent research and consulting firm devoted to the cloud and data center infrastructure services markets, particularly in the hyperscale value chain. He specializes in the data center infrastructure market and leads both coverage of the APAC region and the building of Structure Research’s proprietary market share data.