In the first 30 years of my career, I had the privilege of implementing over $10B of digital infrastructure across three continents. My focus was to drive innovations to enable performance, efficiency and sustainability at scale for the companies I worked for. Over the last three years I have spent the majority of my time obsessing on the connection between efficiency and sustainability in data centers. While I believe the digital infrastructure industry has done a good job raising the priority and taking action in both areas, we are not addressing the real issue. The disconnect between the data center facilities we build and the platforms that utilize them is significant. As I dug deeper into this topic I found that my own actions for the first three decades of my career contributed to this problem. The intent of my article is to address the elephant in the room and propose a solution to solve it.

MARKET CONSTRAINTS

In August of 2022 I attended a conference in Boulder, CO. It was hosted by Cowen Inc, a financial services company with a focus on many areas of digital infrastructure. It was a great conference with many sessions including discussions on the importance of the iMasons Climate Accord to our community.

For me, there was one session at the conference that really stood out. It was the report by Patrick Lynch, Managing Director at CBRE, on the US data center market conditions. Their report showed that vacancy is at an all-time low in every primary market. Demand is outpacing what the supply chain can deliver. Absorption is high. This means there are utility power constraints in almost every market. The most prevalent was Loudon County in Northern Virginia. There is 2,000 MW of inventory with a vacancy rate of 1.9%. This included over 400MW of new capacity added in the last 12 months. To put this in perspective, there was more data center power capacity added in Loudoun County last year than the total data center capacity that exists on the African continent.

This year companies have responded to the demand in Loudon County with almost 1,000MW of new capacity either under construction or pre-committed by customers before shovels have even hit the dirt.

From an economic development standpoint this is ideal. Demand is high, investors are pouring money into the sector and suppliers are moving faster than ever to meet it.

Now the rub. In Q2/2022 Dominion Energy dropped a bombshell. They said they are unable to deliver new power capacity in Loudon County for a minimum of 2 years. It was caused by limitations on installing transmission lines to get the power where it needed to be. Speculation continued with some estimating it could be 5 years before some areas receive more capacity. This was a shock to the system as billions of investment dollars are in motion to build capacity that won’t be able to be powered up. Previous power delivery commitments that had justified the investments were now at risk. Companies are scrambling to find solutions around the constraint.

One month prior to the Cowen event I participated in Biznow’s DICE East conference in Reston, VA. Buddy Rizer, Executive Director of Economic Development for Loudoun County, was the keynote speaker. He shared that Loudoun County is the largest data center market in the world with 2,000MW of deployed power capacity. The economic development program they created over a decade ago has become a reference model for most of the data center markets around the world.

After Buddy’s presentation, Jim Weinheimer and I had a chance to catch up with him one on one. We wanted to dig in further on what was shared about the Northern Virginia market and the current constraints. He said that of the 2,000MW of supply in Loudoun County only 1,200MW is consumed. He also said that this 60% load profile has been consistent over time. That means 40% of energy supply in the largest data center market in the world is never used. What surprised me was that with the limitations on new capacity, no one was focused on the 800MW that is wasted every day. There seems to be acceptance that 60% utilization is ok.

A few weeks after the Biznow conference, there was another shock to the system. Northern Virginia data center consumers started hearing rumors that Dominion was considering a clawback of unused power capacity. Companies in data center alley could be at risk of losing their capacity if they did not use it.

While the clawback concept is new for the digital infrastructure industry, it is a common practice for other sectors served by the utilities. Utilities oversubscribe power based on future forecasts and trailing 12 month load profiles. They time the addition of new power to match expected use. One element of this strategy includes the claw back of power from manufacturing, logistics, and other large consumers if they do not use it. This is understandable as it is very expensive for utilities to build and operate power plants and balance the supply and demand of the power grid to ensure reliability. Like data centers, they want to drive efficiency and reliability and maximize the return on their investments.

With this context I decided to test a theory at the Cowen event. While I knew the answer, I wanted to spark the debate. The CBRE meeting had a mixture of suppliers, buyers, investors and market influencers. They represented the supply side of the market and had decision authority on what investments were made, what capacity was delivered and what metrics they would measure success upon.

I asked the room if anyone measures utilization of the allocated power capacity in data centers.

At first the question caused an awkward silence but then the group jumped in. The response was what I expected. While they do measure overall power utilization of their data centers, it is not shared publicly. The room agreed that colo’s are at the mercy of the customer that contracts the power. The colo delivers the capacity but it is up to the end user on how they use it.

THE RESULTS OF PUE

In September of 2021, InterGlobix Magazine published Issue 7 with a cover story on Christian Belady. It highlighted his leadership in driving efficiency in digital infrastructure. One of his most impactful industry contributions was the Power Usage Effectiveness (PUE) metric that he created. PUE measures the amount of power used by the IT workload against the amount used to power and cool it. The closer to 1 the more efficient you are. Over the last decade, the industry has driven PUEs from an average of over 2 to under 1.2 with Joe Kava’s team at Google leading the industry with a trailing 12 month average of 1.1. The result from the application of the PUE metric has been dramatic.

In 2008 it was predicted that data centers could consume up to 10% of global power over the next decade. Thankfully, this increase did not materialize because of two key factors. The gains from Moore’s law and the application of PUE.

Over the last decade, CPU advancements coupled with virtualization have delivered more than 60x the performance for the same watt of power. Compounding that benefit were the reductions in power consumption through the adoption of PUE. The result? Digital Infrastructure capacity more than tripled but the global power consumption has remained below 3%. The industry successfully flattened the power consumption curve.

While this outcome should be celebrated, we are still missing the bigger picture. The proverbial elephant in the room. Our industry has accepted that the 1 in PUE is 100% utilized. It is not. The majority of the power capacity we build in data centers is not used. Thousands of Megawatts remain idle and hundreds of billions of dollars of investment are not yielding the returns they could. This is not sustainable economically or ecologically.

My day job is the CEO of a startup company called Cato Digital. Our M9 software unlocks stranded power capacity in data centers by virtualizing the power plane. To put it simply, we enable safe oversubscription of power in data centers by offering alternate SLA products and the mechanism to enforce them. This allows colos to increase the amount of sellable capacity at a lower price while maintaining their margins. It allows the customers to rightsize their workloads, increasing efficiency and lower costs like they do in the cloud. The result is increased utilization, efficiency, less waste and increased revenue.

One of the key elements of our strategy was to align the supplier and the buyer on the mutual benefits of this solution. While this concept is new for data centers, it happens every day in AWS, GCP and Azure. Over the last decade, cloud consumers have developed abstraction layers that allow them to dynamically move workloads to take advantage of various cloud capacity offerings. They rightsize their cloud infrastructure consumption and lower their costs. Cloud service providers have also capitalized on this strategy, increasing utilization by over subscribing the users of their systems. Because of this, cloud players lead the market on utilization of capacity with some exceeding 80% in their own purpose built data centers.

Unfortunately, adoption of power virtualization in colocation data centers has been slow and the gains have not materialized. Average power utilization in colos remains between 50-60% even in new builds.

The reasons for this may surprise you as none of them are technical.

UNINTENDED CONSEQUENCES

As I shared at the beginning of this article, I spent 30 years on the buyings side driving over $10B of Infrastructure projects across 3 continents. When I crossed over to the supply side in 2019, I realized that my motivation to deliver benefits for my previous employers had unintended consequences. I unknowingly contributed to the issue we are facing today.

I believe low power utilization in colo data centers is caused by three factors. Procurement, Risk Management and Real Estate.

Procurement

Procurement teams are tasked to secure beneficial terms for their employer. Almost all of these buyers have specific checklists they follow. At Sun Microsystems, Ebay, PayPal and Uber, we tasked the procurement teams to secure dedicated data center capacity with maximum efficiency, high uptime and at the lowest cost. The result was an RFP process that drove these specific requirements. This made the suppliers deliver exactly what we requested. What we received was dedicated capacity at low costs whether we used it or not. At Uber we would contract zones that were between 5MW to 10MW. Even with internal efficiency goals, we would use a maximum of 60% of the power capacity over the contracted term.

Looking back, it is clear to me that we lacked a holistic measurement to drive the right outcome. All of the teams were focused on efficiency, but they managed and measured it in different ways. Each team also embedded resiliency assumptions into their deployments. This meant every layer buffered their capacity needs compounding the problem.

The data center team buffered power capacity to ensure up time. The compute team buffered shared resource capacity to ensure they could cover bursts and workload changes. The platform teams buffered for new feature roll outs. The Site Reliability Engineering teams buffered overall capacity to ensure uptime of services and applications.

For new sites, the data center team provided the procurement teams with the forecasted power ramp over the contract term. We also required the colo to provide dedicated capacity. This meant the colo had to build the total power capacity but could not share this capacity with other users. Procurement pushed this in the RFP process unknowingly driving the inefficiency. The result was 60% utilization of power at best.

Risk Management

The primary reason for capacity buffers is mitigating potential risks to the business. Teams planned for rapid increases in consumption (peak consumption and bursts), local failures and regional faults. They wanted to have headroom to ensure they never impacted the service if there was an outage or an unscheduled increase in consumption.

While this was a logical approach, the misalignment of the different teams causes excessive waste. This waste was clearly evident when we experienced a full region fault at Uber.

Uber split the global demand of rideshare, eats and other business units across two regions in the United States. Half of the global cities were served from the west, half were served from the east. In 2018 we experienced an outage that caused the entire west coast to fail over to the east. At that time Uber was delivering over 15 million trips a day, putting a significant load on the infrastructure. When we lost the west, half of Uber’s global workload immediately shifted to the east region. Within 60 seconds the east region workload doubled. The team braced for a significant surge on the infrastructure and data center power draw.

Ironically, the east region data center power consumption increased less than 10% which was within standard deviation of daily power consumption fluctuation. The worst case scenario had manifested but it was barely a blip on the graphs. They still had more than 30% headroom left. The safety buffers that each team had implemented had compounded the inefficiency.

Now think about how many companies around the world have the same infrastructure risk mitigation strategy and compounding capacity buffers. With this in mind, it’s much easier to understand why colos have less than 60% utilization and no current mechanism to change it.

Real Estate Investment Trust

The final reason for this inefficiency also surprised me. The majority of the colocation companies around the world are structured as as Real Estate Investment Trusts (REIT). A REIT must Invest at least 75% of its total assets in real estate and derive at least 75% of its gross income from rents from real property, interest on mortgages financing real property or from sales of real estate. This means REITs reinvest 75% of their income back into assets. REIT investor’s primary metric is occupancy, not utilization. When a data center is “sold out”, meaning that all of the critical capacity built has been contracted, the REIT moves on to the next asset. They have fulfilled the REIT requirements delivering long-term occupancy and consistent returns.

I want to be clear that this doesn’t mean that colo companies don’t care about efficiency. Quite to the contrary. They would rather have higher utilization as their efficiency would increase, their costs would decrease, maintaining or increasing margin and maximizing the investment of their shareholders. As outlined earlier, the problem is that tenants control the consumption and their investors are focused on different metrics.

DRIVING BEHAVIOR

In Issue 8 of InterGlobix Magazine I wrote an article that defined the digital infrastructure industry. My goal was to have us align on a common definition and create a starting point in which to measure progress.

One of the key points of this article was that over 36,000 MW of global data center power capacity is unused. We have inflicted this inefficiency upon ourselves. It is a result of legacy processes and business structures that I outlined in this article.

But fear not, there is a solution to this problem. We have seen the results when we measure the right thing. PUE adoption significantly reduced waste flattening the power consumption curve over the last decade. It’s time for us to step back and measure the entire system and drive a similar result.

Power Capacity Effectiveness

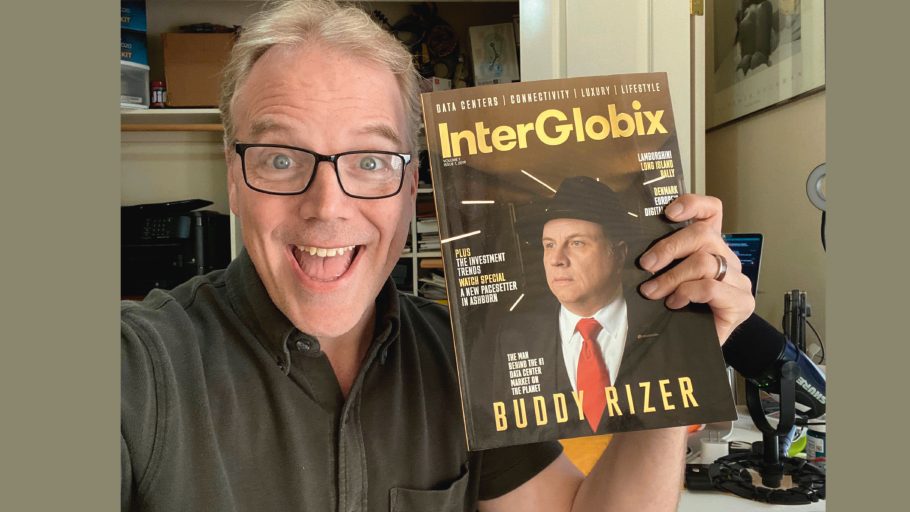

The new metric I am proposing is called Power Capacity Effectiveness (PCE). It is a simple measure of total power capacity consumed over the total power capacity built.

PCE = Total Power Consumed / Total Power Capacity Installed

PCE will work for any data center design of any size in any part of the world. For example, if I deploy a four-makes-three power design with 1.5MW building blocks, I will have 6MW of total power with 4.5MW of critical power delivered to tenants. At a PUE of 1.3, I will have 1.8MW of additional capacity to run it. That makes 7.8MW of total capacity built. If the tenant uses 53% of the contracted power, they will consume 2,385kW. A PUE of 1.3 will add an additional 715kW to that consumption. That means the PCE is 39% (3,101kW / 7,800kW).

PCE puts the onus of overall system efficiency on both the colo and the tenant. The colo will optimize the design to minimize built capacity while meeting required SLAs. The tenant will optimize workloads to maximize utilization of contracted power under those SLAs. In the scenario above, the maximum PCE would be 80% (6,300kW / 7,800kW).

To achieve these levels, companies will have to adopt new ways of deploying and using data center capacity. There are some basic steps that can be taken to increase utilization now. Eliminating multiple buffers in the stack will reclaim a sizable amount of waste. After that, oversubscription, like in cloud, will be required to push PCE higher. Multi-tenant data center customers will need to share UPS capacity. Software architecture leveraging multi-zone regions requiring less resiliency from the data center along with alignment of application services to variable SLAs will become the norm. This practice is not new. It happens every day in cloud deployments. Embracing solutions like the M9 software we build at Cato Digital will help these implementations come to life in colos.

I expect heavy debate about the implementation of PCE. As you contemplate the metric, I encourage you to compare it to PUE. When PUE first came out, the majority of the industry said there was no way they would share that information. It was proprietary and could be harmful to sales. What happened was the opposite. Companies started to measure it, tune it and publish it. Designs changed, products were tuned and the numbers continued to drop. Low PUE became a competitive advantage with companies winning deals because of their PUE results. I expect similar results from PCE. My hope is that RFPs in the future include minimum PCE requirements with a collaborative approach by the colo and the tenant to achieve them.

iMASONS CLIMATE ACCORD

In Issue 9 of InterGlobix Magazine we shared how the digital infrastructure industry is uniting on carbon reduction through the iMasons Climate Accord. We have 170 companies aligned on reducing carbon globally. This consortium of companies has a combined market cap of over 6 trillion US dollars. The buying power of this group is massive. They will change the direction of the industry by leading with their wallets.

From my perspective, the fact that close to 50% of the capacity we build is never used is unacceptable. We now know why that is and can’t in good conscience afford to remain complacent. PCE is a means to drive a behavior change by challenging the status quo on both the colo and tenant. If applied, REIT structures will elevate PCE as a performance measurement. Colo tenants will be motivated to maximize their utilization by addressing the compounding buffers and risk mitigation strategies that have persisted for decades.

The result will be higher efficiency for all involved. That will lead to higher margins for the colo companies, lower costs for tenants and an overall reduction in embodied carbon in support of the iMasons Climate Accord.

If we are going to move aggressively to tackle climate change as an industry, we need to have our own house in order. PCE can drive behavior change and accelerate the schedule for us to achieve our sustainability goals.

Let the competition being. 🙂

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Dean Nelson is CEO of Cato Digital and the Founder & Chairman of Infrastructure Masons. His 35-year career includes leadership positions at Sun Microsystems, Allegro Networks, eBay, PayPal, and Uber. Dean has deployed 10 billion USD in digital infrastructure across four contents. Since its founding in 2016, iMasons has amassed a global membership representing over 200 billion USD in infrastructure projects spanning 130 countries.